This research is being conducted by Dr Annemie Stimie Behr at the University of South Africa (UNISA).

Jewish history in South Africa is generally linked to the careers and legacies of individuals. Political role-players include Joe Slovo and Helen Suzman, while cultural personages include Nadine Gordimer and Irma Stern. With the exception of Johnny Clegg, few Jewish music figures enjoy the same recognition bestowed on their political and literary counterparts, despite their active participation in South Africa’s musical life. My research is arguably the first that seeks to uncover musical meanings of the Jewish community as a cultural group, thus departing from this generalized focus on Jewish individuals as metonyms for Jewish history. In this way, I am giving voice to a silent history.

The research started as a PhD-project, which I conducted at Stellenbosch University between 2015 and 2019. A by-product of the PhD project is a database of music reportage that is currently available on Stellenbosch University’s digital repository and that is compiled in collaboration with the National Library of South Africa. The objective of this database-project is to create an inclusive and wide-reaching digital archive of South African Jewish writing about music during the twentieth century. At present, the database houses 4964 music-related items that appear in the South African Jewish Chronicle and the Zionist Record newspaper publications of between 1905 and 1948.

The scope of content on this database is wide, since the criteria for selecting music-items was to be as inclusive as possible. It includes articles, reviews, opinion-pieces, letters and advertisements. The content does not revolve around a single genre. Instances dealing with ‘Jewish’ music, entertainment music, film music, stage music and Western art music were all included. For this reason, the collection speaks to many disciplines, including theater studies, film studies, popular music studies, Jewish cultural studies, etc. Many reports on social gatherings or religious events (i.e. Zionist gatherings or synagogue services) briefly referenced musical activities. These items were also included, since they make for a rich reading of music’s place and function in social practices. In its current state, the collection is already a valuable resource that researchers consult, which means that the database is already giving voice to a silent history. However, my impression is that there is another, very different layer of silence – a silence caused by the representation of data – that needs to be broken. Online, the format of this database is determined by traditional, academic conventions, which rely on conventional structures of metadata. The result is a rather dry, academic presentation of material. My concern is that many end-users may not find this kind of presentation inviting.

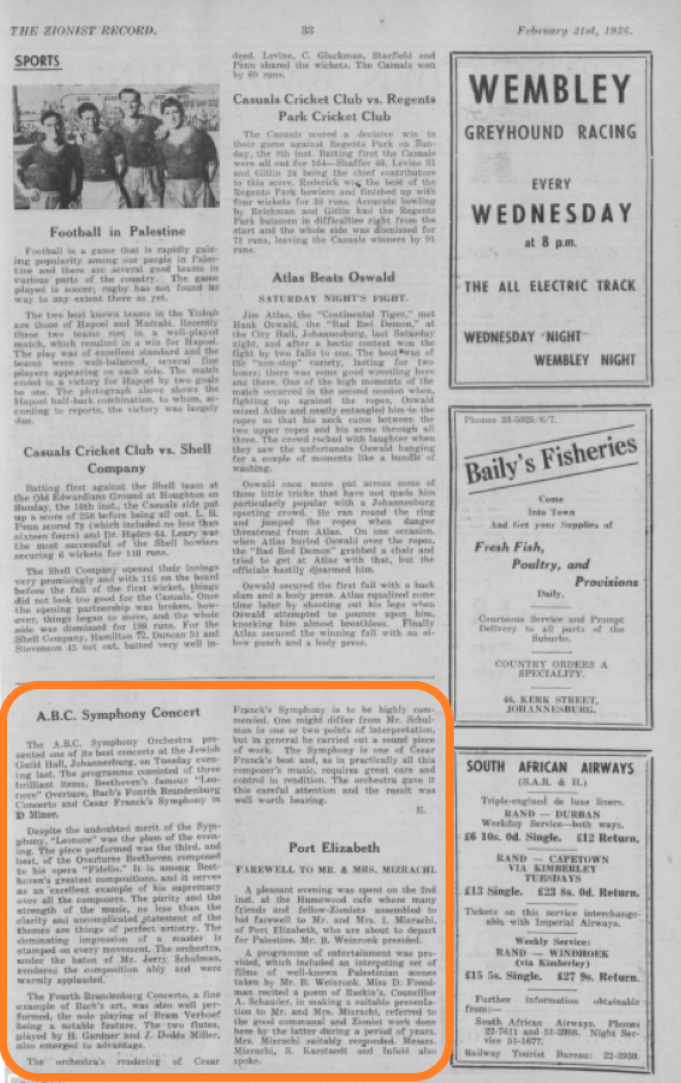

A second concern pertains to the fragmentary nature of the data itself. For instance, while complete pages were scanned and uploaded to the database, the relevant music-item on that page would in most cases only be a small clipping (or several small clippings) on that

page, which the end-user may not easily find.

From the approximately 5000 PDF-items on the database, I systematically created a sample of 333 articles, which then formed the final corpus of texts that I analysed in my PhD-thesis entitled Constructing history from music reportage: Jewish musical life in South Africa, 1930-1948. These 333 articles were transferred to the qualitative data analysis software programme Atlas.ti, where they were sorted into document groups according to their metadata (for each publication and for each year). The software was primarily used to implement coding procedures as prescribed by the methodology of content analysis. My coding structure is divided into two parts: an index and themes. Index codes collect quotations in the material that on the surface appear to have little qualitative value. These quotations populate the historical record with content responding to questions of who, what, where and when. Much of this information could have been extracted with Named Entity Recognition technologies, which is not included in the Atlas.ti package. Themes were identified in four geo-historical clusters that have specific significance for the South African Jewish community: England, Russia, Germany and Palestine. The coding showed that notions of citizenship tend to reference England (South Africa in the early twentieth century was still a colony), whereas ideas of Zionism unsurprisingly speaks of Palestine. Through these codes, then, it becomes possible to trace musical histories in relation to either citizenship or Zionism (or both). Apart from these codes, the software also has an array of annotation tools, which allows the analyst to write memo’s and comments which could include references to relevant secondary sources and/or create links with open data sites like Wikipedia or YouTube. So, for instance, while there was no recording made of the 1930 Victor Chenkin performance in Cape Town, there are some Victor Chenkin recordings posted on YouTube, which could give readers an impression of the performance that the author, Josephus, describes.

For me, these codes and annotation tools opens the data in ways that end-users of the current digital database cannot yet experience. Yet it is possible to open the data with the added codes and annotation to a larger public, since the project can be exported from Atlas.ti in QDA-XML format and can therefore be published online as a linked open data-set. The challenge, however, is that this coding was done on a small portion of the data-set and that coding the rest of the material is, in my opinion, unnecessarily resource intensive – it is slow and laborious. I am therefore investigating the possibilities of submitting the current data-set to a process of machine learning, thereby creating a machine that could continue and conclude the coding of the remaining material in my data-set. Once the coding is done, the data-set can be structured, made visually attractive and published online in ways that would enable interested parties to explore the material with the help of an array of filters, keywords, themes and text-search functions.

Using the South African Jewish Music Articles database as a prototype, I am currently on a quest to explore in Digital Humanities the potential and possibilities of curating online archives of subject-specific newspaper-clippings in ways that would make them even more accessible and user-friendly. Attending the Digital Humanities – African Perspective workshop was my first foray on this quest, and a highly productive one. Not only was I introduced to a vast amount of resources and digital tools that could point the way forward for this project, I also became acquainted with colleagues who have different, but complementary skills in the field of Digital Humanities. Opportunities for co-creating are endless. Collaborating with Digital Heritage scholars, for instance, hold much promise for curating online collections in the African context. Few institutions in South Africa host databases in their repositories in alternative formats. By teaching this digital collection to sing, the hope is to affect a shift in digital collections practices in South Africa (and Africa at large) that would go beyond merely giving voice to silent histories.