Silent Histories: Digital Representations of Cultural Heritage in Africa

The notion that Africa has no history is no longer accepted: the continent’s history is inexhaustible and its heritage is as rich as it is abundant. The perception of Africa being dark and primordial can no longer be tolerated: the continent is not only reclaiming its legitimate inheritance, but also creating its own authentic modernities. In the latter venture of creating an African modernity, the digital is becoming increasingly important. In this publication, we intentionally contribute to this project as scholars in the Digital Humanities.

The notion that Africa has no history is no longer accepted: the continent’s history is inexhaustible and its heritage is as rich as it is abundant. The perception of Africa being dark and primordial can no longer be tolerated: the continent is not only reclaiming its legitimate inheritance, but also creating its own authentic modernities. In the latter venture of creating an African modernity, the digital is becoming increasingly important. In this publication, we intentionally contribute to this project as scholars in the Digital Humanities.

We collectively reflect, through our individual projects, on the imperatives of digital representations of cultural heritage in Africa. Our projects highlight the vulnerability of cultural heritage, whether tangible or intangible. Potential hazards include environmental change and natural disasters, the ravages of time, wilful destruction, cultural terrorism, wars, mis-management, mining and climate change. We risk losing valuable cultural, archaeological, historical and anthropological insights into our past and into our present, whether through direct physical damage and degradation or through fallible human memory and generational divides. This is particularly relevant to Africa, where cultural heritage has not been systematically documented for centuries.

Our projects examine histories that are silent in one way or another. Some have never been heard (such as social practices of the Negede Wayto community in Ethiopia or the musical life of a Jewish community in South Africa), while other historical voices are in decay (the Owl House in the South African Karoo). Some histories have been violently silenced (Kenya’s colonial detention camps); and others are begging for new ways of sounding its celebration (Eyo Festivals in Nigeria and Michael Moerane’s art music in South Africa).

Each project raises unique questions about the imperatives of representing African cultural heritage in digital contexts. We found that multimodal approaches are far more beneficial to Africa’s dynamic cultural heritage than linear ones. A representation of Eyo festival won’t benefit as much from a static approach as it will to a multimodal, participatory approach. The Owl House project, too, benefits from its multimedia structure and the layers of information that contextualize and situates it in its milieu. Digital representations of music history in South Africa are still developing new modes in which to sing, and socio-cultural representations of conflict resolution in Africa can only find full representation through digital multimodality. Digital reconstructions of detention camps in Kenya create a unique platform for communal collaboration and engagement, which bridges the gap between intangible heritage (personal memories) and tangible history (architectural structures).

In our projects, we note the particularities of the African context that necessitates our methodological approaches and strategies to depart from normative Western ones. This puts into motion simultaneous processes of learning and unlearning: learning the conventions of the field of Digital Humanities, and unlearning the preferred modes that undermine African representation. We do this, as our projects demonstrate, by creatively engaging digital methodologies and various modes of digital representation. Digital Humanities also creates for us the necessary conditions to tap into the orality and materiality of our cultural heritage. It enables scholars of Africa to give voice to silent cultural archives using modes that resonate with innate African qualities and features by, for instance, favouring the speaking voice over written text.

The power that we have, as Digital Humanities practitioners working in Africa, is to connect ourselves, through our projects, with our local contexts as well as with the larger continent. All of us contribute to developing a unique African modernity using the digital as an invaluable tool.

A Vanishing Collection in Southern Africa: Digitising the Collection of the Owl House – Sarah Schäfer

Somewhere in the arid landscape of the South African Karoo is a tiny village named Nieu Bethesda. Here lived Helen Martins, whose was only recognised posthumously as an artist, and who is today known as an Outsider Artist. …My research, through interviews with participants who engaged with a digitally curated collection, showed that people appreciate different layers of information, and they also appreciate multimedia being used where it is relevant. An example of this is a pair of shoes, which several participants were drawn to because of the biographical details that were included about an accidental toe amputation. Participants found the details quite bizarre, which made the artefact stand out.

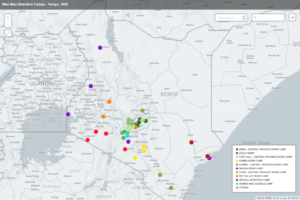

Dialogues on Detention: Towards a framework for community co-production in visualizing silenced histories using 3D reconstructions -The case of Kenya’s colonial detention camps – Chao Tayiana

This research explores the suitability of digital technologies in creating awareness and participation with the history of detention camps In Kenya. More than 100 detention camps and emergency villages were set up and operated by the colonial government between 1952 – 1960. Today, very little is known on the history of these camps or where they were located. This research proposes to use digital reconstructions as an opportunity to start a conversation that aims to be dynamic and fluid (as opposed to ‘ending’ a conversation by presenting digital reconstructions as being authentic and final).

This research explores the suitability of digital technologies in creating awareness and participation with the history of detention camps In Kenya. More than 100 detention camps and emergency villages were set up and operated by the colonial government between 1952 – 1960. Today, very little is known on the history of these camps or where they were located. This research proposes to use digital reconstructions as an opportunity to start a conversation that aims to be dynamic and fluid (as opposed to ‘ending’ a conversation by presenting digital reconstructions as being authentic and final).

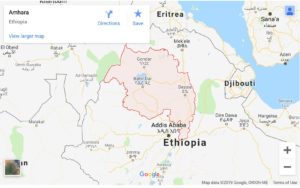

Indigenous Conflict Resolution Practices: The case of the Negede Wayto community in the Amhara Region of Ethiopia – Birhanu Mekonnen

My study explores the indigenous conflict management practice of the Negede Wayto community, which is found in the Amhara Regional State in Ethiopia. Specifically, the community lies at the shores of Lake Tana. The history of the Negede Wayto community and its cultural practices has been silenced for many years. Surprisingly, members of the community are socially and economically marginalized to the extent that they couldn’t be entitled to land in their place of origin.

My study explores the indigenous conflict management practice of the Negede Wayto community, which is found in the Amhara Regional State in Ethiopia. Specifically, the community lies at the shores of Lake Tana. The history of the Negede Wayto community and its cultural practices has been silenced for many years. Surprisingly, members of the community are socially and economically marginalized to the extent that they couldn’t be entitled to land in their place of origin.

Documentation and Digitisation of Festival in Nigeria: A Case Study of Eyo Festival – Felix Oke

Festivals are significant events in the social and cultural reality of apeople. To preserve cultural heritage, specialists capture what happens before, during, and after a festival by interviewing participants, taking photographs and recording audio and video of the event, etc. For example,Pelu Awofeso has documented the Lagos Eyo Festival (also known as the Adamo Orisha Play) in his work White Lagos: A Definitive and Visual Guide to the Eyo Festival,

A silent history and an un-singing digital collection: The South African Jewish Music Articles database – Annemie Behr

My research is arguably the first that seeks to uncover musical meanings of the Jewish community as a cultural group, thus departing from this generalized focus on Jewish individuals as metonyms for Jewish history. In this way, I am giving voice to a silent history.A by-product of my PhD project is a database of music reportage that is currently available

on Stellenbosch University’s digital repository and that is compiled in collaboration with the National Library of South Africa.

Sankofa – Reclamation of the Michael Mosuoe Moerane Musical Heritage

My contribution to the Moerane Digital Critical Edition is to theorise the notion of genre. Of particular interest is how Moerane’s oeuvre reflects a number of South African music genres. In western critical editions, one often finds that it may be ‘easy’ to classify the work of a particular composer into different stylistic categories such as sonata, fugue, cantata, symphony, etc. In the case of Moerane, such demarcations are much more complex as his music embodies other musical genres which are in themselves mixtures of even more genres.